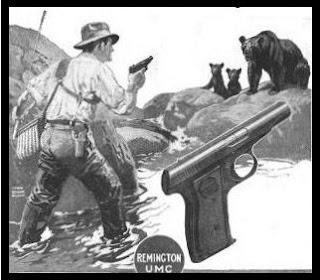

Does anyone really think this is a good idea?

I had to chuckle when I came across this Remington advertisement in an old pre-WWI era sportsman's magazine, advertising the newly-introduced .380 ACP. The .380 ACP, aka 9-mm Short, would not be my first choice for a 150-pound junkie let alone a 400-pound grizzly sow.

“Da Bears.” In particular, da grizzly bear. Even its Latin classification, given it by the naturalist George Ord in 1815, conjures up fear…Ursus horribilis (“terrifying bear”)…and the mountain men would come to call the grizz “Old Ephraim”. Native American tribes afforded these fierce bears the utmost respect; there was greater honor in slaying a grizzly bear than a human foe.

Initially,

Corps of Discovery Captains Lewis and Clark regarded the Indians’ fear and awe

of grizzly bears as rather quaint and actually looked forward to their initial

encounters with the grizzly. After all, the Indians had only bows and arrows

and inferior smoothbore trade muskets while the Corps of Discovery was armed

with the latest greatest military technology in the form of .49-caliber

Pennsylvania-style flintlock Model 1792 Contract Rifles. They opined that the

grizzly would be no match for skilled riflemen.

After the

first few encounters, they changed their minds, with Lewis noting that grizzlies

were “extreemly hard to kill” and Clark describing the grizz as a “verry large

and a turrible looking animal.” Clark and one of the men required a total of

ten shots from their rifles to finally kill a 600-pound grizzly encountered on

May 5, 1805. On May 14th six hunters tried to tackle a grizzly; all

six hit the bear with their rifles on the first go-round, after which the bear

chased some of the men into the river and some into the bushes as they

desperately tried to reload their single-shot front-stuffers. It took a total

of eight hits, the last one a headshot, to kill the bear.

The explorers

of the Corps of Discovery would hardly be the last white men to underestimate

the strength of the grizzly or over-estimate their own firepower.

As previously noted, I find the “fact” that pepper spray has

been statistically “proven” to be 97% effective in stopping bear charges

dubious to say the least. On the other hand, I don’t believe that simple

acquisition of a .500 Smith & Wesson Magnum instantly makes you magically

bear-proof either.

Joe Blow can’t

just waltz into any sporting goods store, purchase some cannon-sized hogleg

revolver with a half-inch bore, and instantly transform himself from

mild-mannered Clark Kent into Dirty Harry Callahan. You have to be familiar, proficient and well-practiced

with your firearm. I remember an article in an outdoor magazine (Fur-Fish-Game, IIRC) many, many years

ago where the author encountered a trout fisherman who was packing a Smith

& Wesson Model 29 for protection against bears. When asked how well the

Magnum shot, the fisherman replied he did not know because he’d never actually fired the gun.

Not to burst

anyone’s bubble, but it really does not

matter how purely “American” your family tree is, your highest score playing Call of Duty, or how many asinine

Quentin Tarantino movies you’ve watched…you were not born with some innate ability to handle a pistol like the

Sundance Kid.

As a pistolero, I consider myself no

more than slightly above average although I started shooting a single-action

Colt .22 revolver in my early teens, was later trained on and qualified expert

with both military and police sidearms over the years, and still get in routine

range practice to this day. In my youth I hunted raccoon with a .22 revolver

and I’ve harvested a great many more mountain grouse on the ground with a .22 pistol

than I have on the wing with a shotgun. Living where we do, I can do a little

plinking whenever I get the urge to. My wife doesn’t do quite as much shooting

as I do, but she also practices regularly and has ten years worth of law

enforcement training, practice and qualification with handguns.

Elmer and Clint: I bought my .44 Magnum because I watched the guy on the right. I kept it because I learned a great deal from the writings of the guy on the left.

Having seen too many Clint Eastwood

movies, I had to purchase a 6-1/2-inch

Model 29 on my 21st birthday. I have no idea how many thousands of

rounds I’ve put through it in the three decades since, but feeding that .44 was

the reason I bought my first reloading kit and I took a whitetail and a mule

deer with it while hunting weapons restricted areas back when I still had two

fully functional eyes and 20/15 vision in the important one. Nowadays, since I

just carry it for protection rather than hunting, I wear a handier 4-inch Model

629, but the principles remain the same.

From a sheer usability standpoint,

one of the first things I did was to install a soft black rubber Hogue Monogrip

on my Model 29 to replace the original S&W Goncalo Alves checkered walnut target-style grips.

I’m an average guy, not quite 5’10” anymore, and apparently my hands and fingers

must be kinda short and stubby compared to Dirty Harry’s, because my hands

never did fit around those wood grips very well. When firing pull-patch Magnum

loads, in fact, the recoil usually required me to readjust my own grip on said walnut

grips after just about every shot. The Hogue grips on the old Model 29 and the

black synthetic S&W grips that came on my 629 fit our hands much better,

offer more positive control, and seem to help a great deal with at least

perceived recoil. I was pleased to later learn that Major John Hatcher had similar

problems with the S&W wood grips way back in 1956, so at least I know it’s

not just me.

The point of certain military and

police training is to become so familiar with particular tasks that muscle

memory and “instinct” take over in a crisis when the brain might temporarily

draw a blank or you’re distracted by shit filling your britches. The nice thing

about revolvers especially is that you can teach yourself much of what you need

to know through dry-fire drills (with Snap-Caps) before honing your technique

with live fire. Dry firing (a whole lot of it, anyway) also helps wear in and

smooth out the double action on a new revolver. No, I don’t stand in front of

the mirror practicing my John Wayne quick draw. I do still occasionally

practice, sometimes at home with dry-firing and sometimes at the range with

live fire, a smooth draw and transition into a firing stance followed

by an accurate double-tap. If you practice smooth, fast will come on its own.

Thankfully I’ve never had to actually

butt heads with a bear, but I have had a few surprise encounters, mostly with

black bears, at close quarters out in the woods. None of these encounters

required any shooting. The one grizzly bluff charge I witnessed fairly close up

was delivered so half-heartedly I knew it was a bluff charge. More often than

not, you really can’t tell if it’s a bluff or not until they’re still coming at

you full bore inside of twenty yards. When it comes to black bears, every

single one of them I’ve personally bumped into immediately swapped ends and

headed for the nearest horizon as fast as they could go as soon as they figured

out what I was. A couple have risen up on their hind legs initially, but that

was just o get a better look at what I was; afterward figuring it out, they

also took off running. I’m glad I never had to shoot but nonetheless was quite

pleased to note that in each and every encounter my revolver just seemed to

appear in my hands, aimed and ready, before I gave the action any deliberate

conscious thought. That’s what muscle memory is for.

Even if you

personally happen to be some kind of uberpistolero

whose gun play makes Clint Eastwood’s Man With No Name in A Fistful of Dollars look like a lame sloth on Quaaludes, not all

handguns are created equal and when it comes to grizzlies heeding Robert

Ruark’s advice to Use Enough Gun is

critical.

Use as much gun as you can effectively manage.

I carry a

compact .45 ACP for social occasions and wouldn’t want anything but an

automatic against two-legged threats. I honestly never understood why American

law enforcement agencies clung to the revolver as long as they did. As nice as

it might be to have a semi-auto, common defensive handgun calibers like the

9x19mm Parabellum, .40 S&W, .45 ACP and even the much-touted 10mm aren’t really

enough gun against a big bruin in a situation in which you are quite literally

betting your life.

There’s an

incredible true instance (Bella Twin of Slave

Lake, Alberta in

1953) of a Canadian woman killing an extremely large grizzly bear with a .22

Long Rifle. While this proves that it can be done, it’s not something any sane

person would set out to do deliberately and/or on a regular basis.

No matter how

big your bore, however, bullet selection is still extremely important. The most

commonly available defensive pistol loads are some form of hollowpoint bullet. A

hollowpoint is designed to expand quickly upon contact with the target,

transferring its energy into the target itself and creating a larger wound

cavity. In the grand scheme of things, and especially against two-legged

predators, this is greatly desirable, but it is not necessarily universally so.

Against a big bear’s thick skull, tough hide, large and dense bones, and

multiple stout layers of ropy muscle and watery fat, you need enough penetration

for the bullet to reach something vital.

Case in point,

the first time I hunted deer with a .44 Mag, I connected on a rather long

(75-80 yards) shot on a forkhorn mulie standing broadside. I was later to find

out that the 240-grain JHP did indeed expand well and transfer energy rapidly.

Unfortunately, my shot was a bit too far forward on the body and hit the

shoulder itself instead of landing right behind it. The JHP hit the shoulder

blade and essentially exploded that entire front quarter, leaving the leg literally

hanging by a thread. Not a single bullet fragment, however, even came close to

penetrating the rib cage beneath and nothing touched the vitals. The result was

a long, slow three quarter mile (away from the truck) stern chase across the

section before the deer ducked down into an arroyo and I was able to get close

enough to administer the coupe de grace.

I also

remember when the Remington Yellow Jacket truncated cone hollowpoint ammo for

the .22 Long Rifle came out. When we used those bullets raccoon hunting, where

the shot was directed right between the eyes, on more than one occasion this

caused the coon to drop from the tree but then hit the ground fighting mad and

tangling with the dogs. Later examination revealed that sometimes the

hollowpoint would mushroom flat against the exterior of the coon skull inside

the hide but not penetrate it. Once upon a time we also needed to put down an

injured feeder pig weighing perhaps 125-150 pounds. At a range of only about

three or four feet, I drilled him neatly between the eyes with an 85-grain .32

S&W Long jacketed hollowpoint. He just ran off squealing and was later

dispatched with a .22 Long Rifle behind the ear.

For handguns, the heaviest available

jacketed soft point (JSP) is greatly superior to the jacketed hollow point in

this respect, but a heavy hardcast flat-nosed semi wadcutter is even better.

Hardcast refers to a bullet constructed with a much harder heat-treated lead

alloy which will not easily fragment and/or lose its penetrative power even if

it hits solid bone. Expansion isn’t near as important as penetration with a

handgun slug that cuts a wound channel damn near a half an inch in diameter the

whole way. As Elmer Keith once put it, “A large entrance hole is just as

important as a large exit hole; both let blood out of an animal and cold air

in.

Avoid cowboy action shooting loads

like the plague as bear medicine. Even though some are advertised as

“hardcast”, this sport calls for low recoil which comes hand in hand with low

velocity as well as lead projectiles soft enough to flatten and fall safely to

the dirt after they hit steel targets.

I personally consider the .44 Magnum

a good choice since it is about as powerful a package as the average Joe (or

Joan) can master. Although it never really caught on as a popular cartridge,

the .41 Magnum also comes very close to .44 Mag performance. It’s personally

all the smaller I would go and I still know three guys right around my area who

carry N-frame Smith & Wesson revolvers in this caliber. What may have been in

1971 Dirty Harry’s “most powerful handgun in the world” has long since been

eclipsed in that title by the likes of the .454 Casull, .460 S&W, .475

Linebaugh, .500, etc. Any of these cannonesque calibers would certainly fill

the bill when it comes to bear defense if

you can handle the weapon effectively and, I might add, if it’s not so big

and heavy and cumbersome that you tend not to carry it and thus wind up at the

moment of truth armed only with a pocket knife and a nearby rock.

Beyond a certain point, bigger does not

always necessarily equate to better. My wife and I once watched a guy at the

range playing with his brand-new X-Frame .500 Smith & Wesson Magnum. It had

a 10-1/2-inch barrel, a variable power Burris 2-7x32mm scope mounted atop it, and

sling swivels fore and aft for a leather cobra strap. IMHO, when a handgun is

too big to be carried in a holster and has to be slung over the shoulder like a rifle, it’s not really a handgun

anymore. One really would be better off just toting a decent rifle-caliber

carbine at that point.

1 comment:

While you scoff at the idea in your post, I think that it would be a rather clever tactic to shoot a grizzly with a .380 in the hopes that the beast would become so cross that it might make a mistake.

Post a Comment