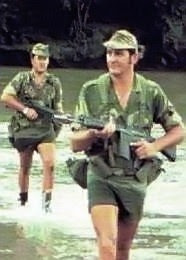

Light forces are undaunted by terrain. Terrain is viewed as an ally, a combat multiplier for the light infantryman. Light forces are terrain-oriented. Very little terrain is impassable to true light infantry.

Light infantry does best when it lives on, in and off the land. It must be comfortable “in the bush.”

Conventional tactics are no good for light forces.

Light infantry forces must be masters of improvisation, familiar with all kinds of weapons, vehicles, landing craft, and so forth.

Light infantry must remain flexible in mind and action, capable of reacting quickly.

Weapons used by light forces must not impose a logistical burden. If equipment cannot be man-packed or mule/donkey-packed, the light infantry generally has little use for it.

Light forces can operate separated from their lines of communications by depending on enemy and indigenous supplies.

Light infantrymen must be able to climb, crawl, swim, ski, snowshoe, rappel, stalk, run and hide.

That is what McMichael, H. John Poole, and William S. Lind mean when they talk about classic light infantry.

Not this.

Unfortunately, as near as I can tell, the modern United States Army defines light infantry as, “Ain’t got no trucks.” Light infantry means you can shove a whole bunch of heavy infantry into C-5s and C-130’s and dump them off somewhere around the globe without combined arms support or logistics and crow that you’ve deployed a division in so many hours. Lacking any real mechanized capability, this light infantry walks wherever they go, but they still have to wear and carry all the crap a mechanized grunt would while riding in a Bradley.

While the infantryman’s load has always been too heavy in the rifleman’s opinion, the modern American Army and Marines have taken gear to completely obscene new heights. Or rather, their “leaders” have forced them to take their gear weight to completely obscene new heights. For Pete’s sake, a mule, bred for centuries as a pack animal, is not supposed to pack over one third of its body weight or it will ruin the animal. You’d probably get arrested for animal cruelty for treating a mule the way the Army treats its infantrymen and the Marines treat their riflemen.

It’s not like the knowledge that over-burdening soldiers is a bad thing was kept secret and came as some big surprise that was suddenly sprung upon America’s military at the last second before the latest deployment. At the turn of the last century, about the time of our Spanish-American War, the Institute William Frederick in Germany was doing in-depth studies and experiments concerning the infantryman’s load. Their conclusion: 48 pounds per man. British studies in the 1920’s concluded that the load should be between 40-45 pounds, or one third of a person’s body weight. Further experiments in the 1930’s suggested dropping the load to 31 pounds! At the end of WWII, the Russians came up with a load of forty pounds after their own studies. Shortly thereafter, American General S.L.A. Marshall concluded that 51 pounds was the optimal soldier’s load in training; for combat, it should never be more than four-fifths of that amount. In 1954, the USMC concluded a grunt should have a load of no more than 55 pounds for a road march, and 40 lbs for combat. Another study in 1971 concluded the Marine should carry 40% of his body weight on the march, and no more than 30% in combat.

Yet today in Iraq and Afghanistan, the supposedly mythical 120-pound ruck is still alive and well in the American military, doing fine, and even reproducing.

As for the other side, a Pakistani Army officer aiding the Mujahedeen during the Soviet-Afghan War noted what little they needed to sustain themselves in combat.

In practical terms the Mujahid can live off the land, or rather from the villages, until the Soviet scorched earth policy became widespread. Even when he takes rations on the march all he needs is nan (flat bread) and tea to sustain him for days on end. The fatty bread is carried wrapped in a blanket, or cloth, and becomes rotten with age, making it the most revolting of meals. Nevertheless, it is eaten. The Mujahideen can walk for days, even weeks, on the minimum of food; then, when the opportunity comes, they will stuff themselves with huge quantities, stocking themselves up like camels for the next journey.

After their weapon, the next most valued possession is their blanket. It is usually a grayish-brown colour, and is used day and night for a wide number of purposes. The Mujahideen uses it as a coat, or cloak, for warmth in winter, or against the wind; they crouch under it to conceal themselves from enemy gunships, as it blends perfectly with the mud or rocks; they sleep on it; they use it as a sack; they spread it on the ground as a table cloth, or upon which to display their wares; often it becomes a makeshift stretcher and sometimes it is a rope; several times a day it becomes their prayer mat.

That sounds pretty silly and pathetic in this age of high-tech gear and precision-guided weaponry, right? Maybe, maybe not. Major General Franklin Hagenbeck said of the Taliban in an interview in 2003: “At night, when these groups heard a Predator or AC-130 coming, they pulled a blanket over themselves to disappear from the night-vision screen. They used low tech to defeat high tech.”

It’s not just guerrillas, either. Professional armies can create real light infantry as well, if they try. During the WWI “Sideshow” in German East Africa, Colonel von Lettow Vorbeck produced some of the greatest light infantry ever known in his Schutztruppe. These were mostly natives trained with Prussian precision, especially in rifle marksmanship.

They marched everywhere they went, which included just about the entire country, with supplies borne by human porters. The Germans had destroyed the railroads to keep the British & their allies from using them, the roads were too rough and muddy for British trucks and armored cars, and the tsetse flies decimated their horses and pack mules. The native Schutztruppe soldiers were largely immune to the diseases of the area, while the white European soldiers succumbed in droves to the myriad of tropical illnesses.

While the regularly-equipped Entendre forces attempting to pursue them ground to a halt, the Schutztruppe not only remained mobile but, with no supply line back to Germany, they became absolute masters of improvisation to remain in the fight. Cloth was spun from native cotton and dyed with the bark of mada trees to make new uniforms. Boots were fashioned from captured saddles and antelope hides. Alcohol “gasoline” was distilled from coconuts and precious salt supplies distilled from the ocean. Without quinine, the German troops would have succumbed to malaria. A substitute was made by boiling the bark of Peruvian trees, a vile-tasting foul brew that the troops christened “Von Lettow Schnapps”.

By the end of the war, with no German supplies whatsoever getting in, the Schutztruppe was equipped and armed almost entirely with captured enemy gear. The Schutztruppe, never numbering more than 10,000 themselves, had tied down some 300,000 Allied troops desperately needed on the Western Front in Europe, and inflicted some 60,000 casualties on the enemy.

The average soldier of the Imperial Japanese Army in WWII was a true light infantryman, as noted by Major C. Patrick Howard among others.

“The usual load an IJA infantryman carried during this period was a steel helmet, a belt with at least one ammunition pouch, a bayonet, a light pack, and an entrenching tool. Soldiers wore a wide variety of footwear, and socks were usually heelless, probably to slow deterioration. To assist in crossing water obstacles, many infantrymen carried the inflatable belt they had worn during the initial amphibious landings. Most soldiers had a 1-yard x 1 1/2-yard camouflage net that they could drape over their bodies and stuff with foliage to render themselves virtually invisible in the jungle. The only piece of equipment that seemed to be standard among all soldiers was the waterproof shelter half, which they wore instead of the army issue raincoat during inclement weather.3 Clearly, the Japanese infantryman’s individual equipment was well suited for a fast-moving, mobile campaign in the tropics.”

As for the Chinese infantryman in Korea, McMichael said he began an offensive with: “3-days' rations, his bedroll, 4 grenades, 100 rounds of ammunition, and a mortar bomb or 2. The Chinese procured some of their food locally, sometimes by force, sometimes by legitimate means. At times, they required villagers to cook for them. Captured UN supplies were also a ready source of ammunition, equipment, and rations; in many cases, the Chinese replenished their stocks after a successful attack. The Chinese also buried supplies when withdrawing from an area with the expectation that the caches would be dug up and used upon their return. In the worst conditions, the CCF soldier learned to do without. His self discipline led him to subsist on meager rations and to forego nonessentials.”

The German Gebirgsjaeger mountain troops of WWII were essentially elite light infantry as well. They had their skis for mobility in the snow; climbing gear for the high mountains. They used any means possible to bring supplies and increase mobility; in addition to their own horses and mules, they used reindeer and sleighs in Finland, camels in Asiatic Russia, suspended tramways in Caucuses mountains, and the little Kettenkrad half-track motorcycle just about everywhere.

But mostly they marched, marched endlessly pursuing the tanks and truck-mounted infantry across Poland and then day after day across the endless steppes of Russia. They could cover fifty kilometers a day, day after day, for weeks on end. How they could manage this was no mystery. Instead of PT consisting of push-ups, sit-ups, and short runs, they marched. James Lucas described the training. “And always the route marches. Some of these were long, lasting all day…Other marches lasted all night through villages lying quiet under the Alpine stars, or across frosty field, kilometre after kilometre…Manoeuvres, exercises, marching and still more marching dominated their lives.”

The Gebirgs also knew how critical weight…or the lack thereof…was, and their manuals continually stressed it. “In selecting equipment to be taken along, the aim must be to achieve the greatest possible economy in weight. The equipment which will permit the individual soldier to maintain his fighting strength must be based on the tactical requirements of the contemplated action… Maximum fire power and mobility are decisive factors in determining the type and number of weapons with which the individual ski trooper should be equipped. The number of heavy weapons to be taken along depends on the facilities for carrying sufficient ammunition. Fewer arms and plenty of ammunition should be the rule.”

The successful British counter-insurgency in Malaya, one of very, very few successes by Western armies in that category, showed that with common sense specialized training the regular line doggie could become a superb light infantryman. British and Commonwealth riflemen went out into the Communist Terrorists’ home turf, deep in the jungle, sometimes for weeks at a time, and, as David Hackworth would say, “Out-G’ed the G’s”.

“The British also devoted some attention to lightening soldiers' loads while on patrol. To further this end, light but appetizing rations were chosen. Because the soldiers looked forward to breakfast and supper on patrol, the command provided palatable food for these meals. In this manner, the light infantry held themselves in position to ambush for some incredibly long periods of time. One platoon of the Green Howards staked out the house of a terrorist food supplier for twenty consecutive nights. 32 In another case, a patrol maintained an ambush for ten days and nights. Given seven days' rations, they simply were told to make them last ten days.”

Fighting Communists in Rhodesia in a tactically successful counter-insurgency, nearly all of the Security Forces were light infantry, including such famous outfits as the Rhodesian Light Infantry and the King’s African Rifles. The most famous Rhodesia Special Forces, uber-light infantry, were the Selous Scouts. Gruelingly trained, they traveled light and did not have an official uniform. Water and ammunition were the two most important items they carried, and in the largest quantities. Favored footwear consisted of rubber-soled hockey boots known as “tackies”. Originally equipped with British Pattern 1958 standard web gear, the Selous Scouts soon developed their own Rhodesian vest that provided light weight, mesh ventilation, and multiple pockets.

An American military observer noted: “Once in the unit, the men are prepared literally to follow terrorist spoor for weeks on end in all types of Rhodesian terrain while living off the land.”

Historically, Americans have been able to create fine light infantry. During the American Revolution, sharp-shooting physically fit frontier riflemen made the best light infantry. A letter from a gentleman in Philadelphia may have over-stated the case a bit when he wrote: “What would a regular army of considerable strength in the forest of America do with one thousand of these men, who want nothing to preserve their health and courage but water from the spring, with a little parched corn, with what they can easily procure in hunting; and who, wrapped in their blankets, in the damp of night, would choose the shade of a tree for their covering, and the earth for their bed."

Poetic license aside, these frontier riflemen were indeed very mobile light infantry. Colonel Daniel Morgan raised a company of riflemen in Virginia and marched them 600 miles to Boston in three weeks. Captain Michael Cresap brought in his company from the Ohio territory, covering 550 miles in only 22 days.

During the War of Northern Aggression, the already poorly-equipped Confederate soldier sometimes stripped away the few comforts he had to march much more swiftly than his opponent.

"The coatee issued in the early days of the war had already given place to a short-waisted and single-breasted jacket. Overcoats were soon discarded. ... Nor did the knapsack long survive. ... But the men still clung to their blankets and waterproof sheets, worn in a roll over their their left shoulder."

These were the indomitable infantrymen of General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, whose uncanny mobility earned them the nickname “foot cavalry”. During the Shenandoah Campaign, in addition to numerous skirmishes and fights, these men also managed to cover some 670 miles in barely over a month and a half.

The way technology had changed between 1862 and 1952 it would hardly seem plausible that the same bedroll Stonewall Jackson’s men wore could still be viable. It could.

Veteran, historian, and author Ralph Zumbro, before he went over to the dark side and became a tanker, tells of the Korean War-vintage 45-pound basic infantry load, and the Horseshoe Roll he carried consisting of: Shelter half, tent pegs, tent pole sections, either a sleeping bag or two wool blankets, one extra set of fatigues. One hank of tent rope, ground cloth or air mattress…We could and did modify this into a Civil War style patrol roll on occasion and they were all different. Mine was usually a shelter half, blanket, patrol munchies (nuts & dried fruit), one or two wet rations (wetpack, canned C-rat, and ONE would run me for 24 hours, and still will) medkit, socks, skivvies, toothbrush & powder, foot-powder, weapon kit, toilet paper..??? That's about it. Need to take modern troops and send the buggers out with that load...Get them used to travelling light. There's nothing there that needs to be dropped…I'd better clarify that roll a bit. It wasn't a short fat sleeping bag in the small of the back. We rolled the shelter half LENGTHWISE...Blankets too, into a LONG sausage, and then slung it over the left shoulder with the ends tied together over the right hip. Stayed out of the way of everything, been around since forever....Drops easy.

With this load, it was understood that the infantry could march twenty miles per day and still be ready for an assault at the end of the march.

The Marine Corps Raiders of WWII were also superb light infantry. They were trained and commanded by Colonel Evans Carlson, who had spent years in China learning guerrilla warfare from Mao’s Communists when they got around to fighting the Japanese. The Raiders' many feats included the famed Long Patrol on Guadalcanal, a month-long 150-mile reconnaissance in force behind Japanese lines. As one enlisted Raider told it, the patrol was indeed no rose garden.

“A bit about our diet. The first several days I subsisted on D rations, an unappetizing chocolate bar fortified with God knows what. This was replaced with the diet of the Chinese 8th Route Army, rice raisins and salt pork. A wise choice under the humid, tropical conditions. It was dry, light in weight and of high caloric value and it withstood the heat and humidity. At the end of day one would build a small fire, I still have the small tightly sealable cylinder containing matches. The liner was removed from my helmet and in the metal portion the salt pork was rendered, then the rice was added, cooked in river water and kicked up with a hand full of raisins. We had the blackest helmets in the entire Corps…Although never verified, fellow Raiders dined on a mongoose and an unfortunate cat. Water was always available from the many rivers and streams. As learned from our Solomon Islanders, a very clean drink could be obtained, by hacking into a segment of a large bamboo plant. No one gained weight on the Long Patrol.”

Another enlisted Raider detailed the minimal gear he carried. “My pack was a gas mask case which held my food, matches, a good supply of dry socks and a bottle of tincture of merthiolate.”

Fast forward to 1982 and the invasion of Grenada. The Army Rangers combat jumped with an average load carried per man of 167 pounds! Here’s how one of the men participating described it: "We attacked to secure the air head. We were like slow moving turtles. My rucksack weighed 120 pounds. I would get up and rush for 10 yards, throw myself down and couldn't get up. I'd rest for 10 to 15 minutes, struggle to get up, go 10 yards, and collapse. After a few rushes, I was physically unable to move, and I am in great shape. Finally, after I got to the assembly area, I shucked my rucksack and was able to fight, but I was totally drained."

Afghanistan, 2003: We had extreme difficulty moving with all our weight. If our movement would have been to relieve a unit in contact or a time sensitive mission we would not have been able to move in a timely manner. It took us 8 hours to move 5 clicks. With just the [Interceptor hard body armor] vest and [Enhanced Tactical Load Bearing Vest or the MOLLE vest] lbv we were easily carrying 80 lbs. Throw on the ruck and you’re sucking.

Even Natick Soldier Center, always known for sugar-coating the hell out of anything that could be considered remotely unflattering to the Army, had to say something: “Most felt they went in too heavy. Soldier load was from 75-110 lbs. Many felt they had too much weight to move efficiently in that terrain at that altitude.”

Additionally, most of the major powers equipped their grunts with web gear designed for mechanized infantry. They weren’t supposed to operate very far, or for very long, from the armored personnel carriers or infantry fighting vehicles which transported them into the big battles that would take place upon the plains of Central Europe. Mech infantry gear came back to bite the British in the butt in the Falklands and especially the Russians in the mountains of Afghanistan.

So the Perfumed Princes of the Pentagon and their pet engineers, physicists, witch doctors, and lawyers, none of whom had ever slept a single night in the field, designed the latest greatest super-secret chocho-fudgie grunt gear. From the sounds of it, they probably would have done better by locking a squad of real grunts in a room with a couple of cases of beer and letting them come up with the new field gear. The Pentagon wonks spent millions and yet before deployment, the grunts have to go out and purchase their own boots, socks, gloves, weapon lights, GPS’s, pistol magazines, linked machine gun ammo carriers, etc. from civilian sporting goods stores.

The latest, greatest waste of defense money was the new MOLLE (MOdular Lightweight Load-carrying Equipment), with a load bearing vest the men loathe and a pack with a plastic frame that breaks if you look at it wrong. I personally have not tried these vests, but the real evaluators, the grunts, would seem to be less than complimentary. I know my stepson in the 82nd, with two tours in Iraq, had very little good to say about them.

These guys don't seem impressed either.

The Army in Afghanistan; First Sergeant: "All personnel involved hated the lbv[MOLLE load bearing vest]; it’s so constricting when you wear it with the vest [ballistic body armor], then when you put a ruck on it cuts off even more circulation."

The Marines in Afghanistan; Major: "We're discovering that the MOLLE is not holding up under pressure. Most of Battalion 3/6 doesn't even wear the vest; they hate the vest. They attach the canteens and all of the magazine pouches and everything directly to the flak jacket, because the vest is just added weight…Now you can't shed the gear and just wear the flak, and that's important when you're crawling around…"

The Marines in Iraq, First Sergeant: "MOLLIE (pack) LBV (load bearing vest) is NOT GOOD [original author’s emphasis]. We put all of our gear on the flak jacket."

The Army in Iraq, Specialist: "The MOLLE ruck is awful. It’s a torture device that you can put stuff in. I bought my own ALICE ruck but was eventually forced to use the issued MOLLE ruck instead."

So now our grunts are not only grossly over-burdened weight wise, but the insane tonnage is also uncomfortable. As a result, our infantry soldiers can barely move. While the Taliban enemy runs circles around our “light” infantry such as the Rangers, 10th Mountain, and Marines at 4-7 miles per hour, our guys, at least in the mountains, are crawling along at one mile per hour or less. It’s awful hard to “close with and destroy” the enemy if you can’t catch him.

Welcome to the heaviest “light” infantry in the history of warfare.

8 comments:

Excellent job there Bawb. Extremely good information and I believe spot on. Pretty much in line with what we have done in the past.

I'm running with a bastardized version of the Brit 58 Pattern webbing now. I'm right on the ragged edge of getting it down to 40 pounds with 72-hour food, shelter and sleeping gear, full six mags, 1 bando, and three quarts of water. I still have to shed a half pound somewhere, but I'm working on it. If it weren't for the fact we live where it can snow or freeze any month of the year, I would be a lot lighter already.

Great stuff. I'm a personal fan of back packing light (even though I haven't done any for some time). My favorite shelter is a cheap tarp secured with 550 cord. You can fashion some impressive weather proof shelters with it. Maybe combine it with a poncho with a liner or a blanket and you're ready to go.

Water is heavy. Carry according natural availability.

Ammo - haven' worked that one out yet and .308 isn't exactly light.

Thanks for the article. It's a keeper.

I had to hunt for it a little, but Viking Preparedness had a similar-themed article last year, about the importance of traveling lightly and the light infantryman. I think your post covers better the stupidly repeated pitfalls of logistics-supported (and bureaucracy-imposed) infantry in our modern world.

Great article! Probably the best I've read in a long time... in the summer time, I use an old Finnish gas mask bag as a haversack, with my bedroll (poncho and liner) strapped to the bottom of it. In the winter it all goes into a medium ALICE pack with some more clothes and a sleeping bag.

Military pilot who had sex with an 11 year-old boy when he was 17!!

A JUNIOR IN HIGH SCHOOL AND AN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL BOY.

As a child he was an aggressive sexual preditor who violated both his brothers both of whom went on to have homosexual experiences.

How long did he continue to think about boys when he masterbated??? In basic training? Into his flight training?

In addition, he is aroused by she-males.

Thank you for your interesting and informative blog. I have enjoyed reading it and appreciate the work you have put into it. Here is some relevant information for you to review .

Kids Tactical Vests

Thank you for your interesting and informative blog. I have enjoyed reading it and appreciate the work you have put into it. Here is some relevant information for you to review .

Toy Machine Guns

Post a Comment